There will be many experienced Irish Setter owners, who are more than familiar with the general requirements of the dog or bitch that has been entrusted to them by their breeders. However, some are not.

The Irish Setter Health website that has been set up and run by members of the South of England Irish Setter Club is a very good place to look for well written, informed advice on the ins and outs of the health of the Irish Setter.

Irish Setter Health – www.irishsetterhealth.info

This site, like many other health pages, is not to put you off purchasing an Irish Setter puppy. In fact it is quite the opposite! It is here to act as a guide, so that you get the healthiest puppy possible from a reputable breeder and if any health scares happen during the life of your new companion, you have the best amount of information available to help that situation.

There are several people in positions at Irish Setter Clubs throughout the UK that are more than willing to give their time and advice/ expertise. They generally converse throughout the year on matters concerning the health and wellbeing of Irish Setters. Annual meetings are also held. This is chaired by the Breed Health Coordinator:

Emeritus Professor Ed Hall, Department of Clinical Veterinary Science, University of Bristol.

The Club representatives or health officers are:

Irish Setter Club of Wales (ISCW): Hefin Jones

Belfast and District Irish Setter Club: Karen McKelvey

Irish Setter Association, England (ISAE): Rosie Dudley

Irish Setter Breeders Club (ISBC): Jo-Anne Parsons

Irish Setter Club of Scotland: Chloe Green and Jenna Sturrock

Midland Irish Setter Society: Lynne Sketchley

North East of England Irish Setter Club: Sally Mohan

South of England Irish Setter Club (SEISC): Meg Webb

Not only do these members meet to discuss on going health issues within the Irish Setter world, but also collaborate with the Kennel Club health team with the on going Breed Health and Conservation Plan (BHCP).

As a Breed, under Kennel Club rules, we are in some cases required, others requested, to carry out certain health tests on Irish Setters, from a young age. These include:

CLAD- Required- DNA test: Canine leucocyte adhesion deficiency | Kennel Club (thekennelclub.org.uk)

PRA RCD1- Required-DNA test – PRA (rcd1) | Dog health | The Kennel Club

PRA RCD4-Requested-DNA test – PRA (rcd4) | Dog health | The Kennel Club

Hip Dysplasia/Hip score- Requested- Hip dysplasia screening scheme | Dog health | Kennel Club (thekennelclub.org.uk)

Eye screening scheme- Requested- Eye screening scheme | Dog health | The Kennel Club

Canine Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency (CLAD) is an inherited immunodeficiency condition, which affects the white blood cells’ ability to fight infection. Affected puppies show infections from a very early age, often with umbilical (navel) infections from birth with other recurring infections of skin, mouth and sores that do not heal. There may be tonsillitis, pneumonia as well as joint and bone problems. These infections usually respond well to antibiotics, but, as soon as they are stopped, the infections return. Inflammation of the gums occurs when the pups are about 2 months old along with swollen jaws. Some joints become swollen, in some cases so much so that movement is difficult. Although it affects different pups to varying degrees, CLAD is inevitably fatal.

CLAD is identical to human LAD and bovine LAD, which has aided research. Primarily, it is known that the mode of inheritance is by a single recessive mutation in a gene that is responsible for controlling a vital part of the function of the white blood cells. This means that puppies have to inherit two copies of the mutant gene, one from its dam and one from its sire. Research on the disease was carried out in England and Scandinavia, where the carrier rate was close to 12%. That meant that 12% of the tested population of Irish Setters was not suffering from and never would suffer from the disease, but could pass on the mutant gene to its pups. Affected dogs are likely to die before reaching breeding age, but mating of two carriers will produce, on average, one affected, two carriers and one clear progeny for every 4 pups.

Irish Setters now have a DNA test for CLAD which has, over time, allowed breeders to apparently eliminate the problem from the breed in the U.K. Since 2007, no Irish Setter that has been tested for CLAD has been found to be either a carrier or affected. Unless a case is made to the K.C. for exceptional circumstances, then no puppy can be registered with the Kennel Club unless it is either hereditarily clear or tested clear.

It is important that if you are considering buying a puppy you check with the breeder to confirm that both the sire and the dam have been DNA tested clear or are hereditarily clear. If not, then the puppy himself needs to have been DNA tested. If not, we recommend you do not buy the puppy. The information is clearly shown on the puppy’s Kennel Club registration papers.

Follow the link to see the list of Irish Setters tested for CLAD in the U.K.

www.thekennelclub.org.uk/item/1142

An Irish Setter dog was imported to the U.K. in 2016 and is confirmed as being a CLAD carrier. We believe there is a second imported dog that is also a CLAD carrier. Neither of these dogs appear on the Kennel Club register of dogs DNA tested for CLAD. It has neen reported that one of these CLAD carriers has been used at stud and therefore, statistically, 50% of his puppies will be carriers increasing the number of carriers in the U.K.In the U.K. it is very easy to become complacent and believe this problem no longer exists, but it obviously does. Responsible breeders do not want CLAD to become a problem in the breed again, so please check that your puppy and parents are CLAD clear.

References

– Immune Deficiency in the Irish Setter (Granulocytophy) SEISC Southern Aspect 1990/1991

Dr Gunilla Trowald-Wigh

– Irish Setter Club of Wales Memorial Lecture 22/2/98

Speaker Dr Gunilla Trowald- Wigh, veterinary clinician from Uppsala University

– Leucocyte adhesion protein deficiency in Irish Setter dogs 1999

Dr Gunilla Trowald –Wigh, Lena Hakansson, Anders Johannisson, Leif Norrgren and Carl Hard af Segerrstad

– Canine Leucocyte Adhesion deficiency (CLAD) in the Irish Setter 2000

Dr Jeff Sampson KC Canine Genetics Co ordinator

One of the health problems people associate with Irish Setters is PRA (Progressive Retinal Atrophy), which is a term for several different forms of hereditary conditions, which lead to blindness and which is found in many breeds of dogs. This was a major problem for the breed in the 1940’s and 1950’s and was the greatest threat to the breed. This eye condition leads to gradually worsening vision and eventual total blindness in both eyes. The condition is hereditary and is carried by a simple autosomal recessive gene.

Early Onset Form

With an early onset form of the disease, puppies may be diagnosed from about 6 weeks and become totally blind by about 12 months. Night blindness is usually noticed first. Owners may notice that the dog is bumping into things in the dark or be unwilling to go outside.

The breed now has a DNA test for PRA rcd 1 mutation. Since the K.C. started its open register in 1995, no dogs that have been tested since then have been diagnosed with PRA rcd1 in the U.K.

By using the DNA test effectively, this particular PRA is no longer a problem for Irish Setters in the U.K. Since January 1st 2010, the Kennel Club will only register Irish Setters that are proven to be clear of PRA-rcd 1 (Progressive Retinal Atrophy), or hereditarily clear of PRA -rcd1 e.g. both parents are clear. This includes imported Irish Setters as well. Do not buy a puppy unless both parents are clear. This is clearly shown on the K.C. registration papers of the puppy. Remember both parents need to be clear, not just one of them.

Why bother to have a PRA rcd 1 clear puppy?

There are several reasons why this is important; the first being that if a pup is clear then it will never get PRA rcd1 and if you decide to breed then its puppies will never get the problem. Responsible breeders have worked very hard to eradicate PRA rcd1 from the breed in UK and want to keep it that way. Also, although you may not be thinking of breeding from your pet at the moment, you may change your mind later and unless both parents are clear from PRA rcd1 then the puppies cannot be registered with the Kennel Club.

In 2014, we were advised that an Irish Setter, in mainland Europe, had been confirmed as being PRA-rcd1 affected and was going blind. In the U.K. it is very easy to become complacent and believe this problem no longer exists, but it obviously does.

Late onset PRA Blindness

Although PRA rcd1 is no longer a problem, it is suggested that you have your dog’s eyes tested at an eye clinic every two years, as there are other forms of PRA being identified.

Late Onset PRA (LOPRA) which, as the name suggests, does not show until the dog is older, has been identified in the breed. A mutation known as rcd4 has now been found, and a DNA test is available (NB. rcd2 and rcd3 are mutations found in other breeds). Time of onset of blindness is variable, but typically later in life.

Recently a mid-onset PRA has been identified, with clinical signs of PRA developing in middle age. The genetic mutation has not yet been identified and research is ongoing.

Please look at “Spotlight on” to see the latest announcements about PRA rcd4 which is the mutation recently identified and for which a DNA test became available from 1st August 2011.

If you believe your Irish Setter has vision problems consult a veterinary ophthalmologist for a diagnosis of PRA. If it is confirmed, then let the health representative of a breed club and your breeder know immediately. They will be able to advise you what to do next as a DNA test will be needed to confirm if it is PRA rcd4.

Any Irish Setter with suspected sight problems can have DNA testing free-of-charge if the sample sent to the Cambridge Genetic Centre is accompanied by a certificate from a veterinary ophthalmologist confirming PRA (Progressive Retinal Atrophy), which is neither rcd1 or rcd4.

The Kennel Club PRA rcd4 Register is updated at the beginning of each month

http://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/item/3915

For pedigrees go to https://irishsetterpedigrees.co.uk/

************

DNA testing scheme for Irish Setters – PRA rcd4

Following consultation with the Irish Setter Breed Health Committee, the Kennel Club has recently approved a new official DNA testing scheme for PRA (rcd-4) in the breed.

Follow the link for further information:http://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/cgi-bin/item.cgi?id=3892&d=pg_dtl_art_news&h=242&f=0

*********

DNA Testing for PRA RCD4 is available

https://www.cagt.co.uk/dna-tests

We advise that all breeding stock is tested before mating.

**************************

Following a meeting between Professor Ed Hall, Chairman of the Breed Health Committee, Dr Cathryn Mellersh. Canine Genetics Research Group Leader from AHT and Dr Jeff Sampson, Genetics consultant to the Kennel Club, we have been advised by Ed Hall that in addition to the 7 dogs which have been identified with PRA rcd4 there are 3 more having “mid-onset” PRA and which do not have rcd1 or rcd4.

To get your dog tested for PRA by an ophthalmologist you will need to see your vet first and ask for a referral to an eye specialist.

10/8/2011

****************

Joint Irish Setter Breed Clubs

Statement on the control of the rcd4 mutation in Irish Setters

The Joint Irish Setter Breed Clubs (JISBC) have drawn up the following guidelines for the control of the recently discovered rcd4 mutation, which causes Late Onset Progressive Retinal Atrophy (LOPRA) in Irish Setters. Whilst it should be stressed that clinical signs of LOPRA usually appear after the age of 9 years, the JISBC still believe it to be a welfare issue, although it is noted that many dogs can cope with blindness.

Data from the Animal Health Trust so far suggest the prevalence of carriers of the rcd4 mutation (i.e. heterozygotes) in the breed is about 42% and therefore the proposed guidelines are considered appropriate at this time. The JISBC recognises the need to maintain genetic diversity within the breed and does not yet recommend a complete ban on breeding using carrier or affected dogs.

However, the principle of these guidelines is that no dogs should be produced that will develop PRA and become blind, and therefore all members of the JISBC agree that:

1. All caring and responsible breeders will test their stock before planning a mating.

- Any rumour and supposition about a dog’s genetic status should be ignored; DNA-testing should be undertaken.

- As DNA-testing is now available, ‘hereditarily clear’ dogs will be produced. However such dogs should still be tested before being used for breeding because of the potential difficulty in proving parentage.

- If the rcd4 status of any stud dog, or its semen, is unknown then the bitch to be mated must be tested and found CLEAR.

2. AFFECTED dogs (i.e. homozygous for the rcd4 mutation) should never be mated with other AFFECTED dogs as all progeny will be AFFECTED.

Thus the following are recommendations about potential matings that the JISBC consider acceptable at this time:

- CLEAR x CLEAR matings are encouraged.

- CLEAR x CARRIER* matings: progeny will, on average, be CLEAR (50%) or CARRIERS (50%) and should be DNA‑tested before breeding.

- CLEAR x AFFECTED* matings: all progeny will be CARRIERS.

* It is recommended that any use of AFFECTED and CARRIER stud-dogs is given serious, cautious consideration by both stud-dog owners and breeders before planning a mating.

Purchasers of any dogs produced by CLEAR x CARRIER and CLEAR x AFFECTED matings should be advised that these dogs will not develop PRA rcd-4, but should not be used for breeding unless tested.

All breeders should note that AFFECTED x CARRIER or CARRIER x CARRIER matings may produce some AFFECTED dogs.

- CARRIER x CARRIER matings will produce, on average, 25% AFFECTED progeny.

- AFFECTED x CARRIER matings will produce, on average, 50% AFFECTED progeny.

Purchasers of any dogs produced by such matings should be advised that some of these dogs may develop PRA rcd-4 and should not be used for breeding unless DNA-tested.

The JISBC will continue to monitor the prevalence of the rcd4 mutation within the breed. However, it is aware that a further PRA mutation that causes blindness at an earlier age (so-called mid-onset PRA) may be present in the breed, but has yet to be confirmed and characterised genetically. Thus control measures for rcd4 may need to be modified if this new form of PRA is prevalent, as the earlier onset of blindness clearly has an even greater welfare implication.

Signed on behalf of the following breed clubs, which endorse and support these recommendations

- Belfast & District Irish Setter Club

- The Irish Setter Association England

- The Irish Setter Breeders Club

- The Irish Setter Club of Scotland

- The Irish Setter Club of Wales

- The Midlands Irish Setter Society

- North-East of England Irish Setter Club

- The South of England Irish Setter Club

Professor E J Hall

Chairman, Irish Setter Breed Clubs Health Coordinator Group

29 February 2012

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Statement from The Animal Health Trust

Progressive Retinal Atrophy in the Irish Setter

Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) is a well-recognised inherited condition that many breeds of dog are predisposed to. The condition is characterised by bilateral degeneration of the retina which causes progressive vision loss that culminates in total blindness. There is no treatment for PRA, of which several genetically distinct forms are recognised, each caused by a different mutation in a specific gene. The various forms of PRA are typically breed-specific, with clinically affected dogs of the same breed usually sharing an identical mutation. Clinically affected dogs of different breeds, however, usually have different mutations, although PRA-mutations can be shared by several breeds.

A mutation for an early-onset form of PRA, known as rcd1, was identified in Irish Setters as long ago as 1993, and is well-documented to affect dogs from a few weeks of age. More recently dogs have been identified with a seemingly different form of PRA that affects dogs later in their lives and is known to be different from rcd1. This alternative form became known as “LOPRA” – for Late-Onset PRA. Unlike rcd1, where all dogs became affected at almost exactly the same age the age of onset of dogs with LOPRA varied, from a few years of age (2-3 yo) up to old age (10-11 yo). It was unclear whether these dogs all shared the same form of PRA or whether there were genetically distinct forms of PRA segregating in this breed.

Mutation Identified

In 2011 geneticists working in the Kennel Club Genetics Centre at the Animal Health Trust identified a recessive mutation that is associated with the development of LOPRA in the Gordon Setter. Owners of Gordon Setters with LOPRA report that their affected dogs develop night blindness in the first instance, which is indicative of a rod-cone degeneration, so we have termed this mutation rcd4 (for rod-cone degeneration 4) to distinguish it from other, previously described, forms of rod-cone degeneration.

Following our work with rcd4 in the Gordon Setter we have found some Irish Setters that have been diagnosed with PRA also carry two copies of the rcd4 mutation. As a result the AHT will make the rcd4 DNA test available to Irish Setters, from August 1st 2011. The DNA test we are offering examines the DNA from each dog being tested for the presence or absence of this precise mutation and is thus a ‘mutation-based test’ and not a ‘linkage-based test’.

Other Forms of PRA

The research we have carried out to identify the rcd4 mutation has revealed that there are at least three forms of PRA segregating in the Irish Setter; rcd1, rcd4 and an additional, third form, that has yet to be identified. We know there is a third form of PRA because of the ten dogs with LOPRA, whose DNA we have been sent to analyse, only 7 have two copies of the rcd4 mutation. The remaining 3 dogs do not carry either the rcd1 or rcd4 mutations, meaning their PRA must be due to another, as yet unidentified, mutation. There is some evidence that this third form of PRA has, on average, an earlier age of onset than rcd4, but we need to examine more dogs before we can be confirm this.

The age at which dogs with the rcd4 mutation develop PRA seems to vary and we know about dogs as young as 4yo and as old as 10yo, that have been diagnosed with LOPRA, and that carry two copies of rcd4 mutation. But it is important to remember that the age at which a dog is diagnosed with PRA can vary according to circumstances, and is not necessarily the same age at which it started to develop PRA. For example, a dog whose PRA is detected at a routine eye examination will have an earlier age of diagnosis than a dog whose PRA was only detected once it started to lose its sight. It is also possible that the dogs that have developed PRA very early also carry the mutation for the third, unidentified, form of PRA (as well as rcd4) and it is this ‘mid onset’ mutation that has caused them to develop PRA at a relatively young age. More research will be required to understand the variability in age of onset more fully.

Our research indicates rcd4 is a common form of PRA among Irish Setters and the development of this test therefore enables breeders to slowly decrease the frequency of an important form of PRA in their lines. However, because we know that at least one other form of LOPRA exists within the breed, we cannot guarantee that any dog will not develop PRA, even if they are clear of the rcd4 mutation.

Rcd4 DNA Test

Breeders using the rcd4 DNA test will be sent results identifying their dog as belonging to one of three categories. In all cases the terms ‘normal’ and ‘mutation’ refer to the position in the DNA where the rcd4 mutation is located; it is not possible to learn anything about any other region of DNA from the rcd4 DNA test.

CLEAR: these dogs have two normal copies of DNA. Clear dogs will not develop PRA as a result of the rcd4 mutation, although we cannot exclude the possibility they might develop PRA due to other mutations they might carry that are not detected by this test.

CARRIER: these dogs have one copy of the mutation and one normal copy of DNA. These dogs will not develop PRA themselves as a result of the rcd4 but they will pass the mutation on to approximately 50% of their offspring. We cannot exclude the possibility that carriers might develop PRA due to other mutations they might carry that are not detected by this test.

GENETICALLY AFFECTED: these dogs have two copies of the rcd4 mutation and will almost certainly develop PRA during their lifetime. The average age of diagnosis for dogs with rcd4 is 10 yo, although there is considerable variation within the breed.

Advice

Our research has demonstrated that the frequency of the rcd4 mutation in Irish Setters is high and approximately 30-40% of dogs might be carriers. The mutation is recessive which means that all dogs can be bred from safely but carriers and genetically affected dogs should only be bred to DNA tested, clear dogs. About half the puppies from any litter that has a carrier parent will themselves be carriers and any dogs from such litters that will be used for breeding should themselves be DNA tested prior to breeding so appropriate mates can be selected. All puppies that have a genetically affected parent will be carriers.

It is advisable for all breeding dogs to have their eyes clinically examined by a veterinary ophthalmologist prior to breeding and throughout their lives, so that any cases of PRA caused by additional mutations can be detected and that newly emerging conditions can be identified.

20/7/2011

*********************

PRA rcd4 (LOPRA) Some questions answered

(please read this alongside the AHT announcement)

I have been asked a number of questions on this subject, and the following answers try to throw light on the current situation.

- What does it mean to be genetically affected but not yet clinically affected by PRA rcd4?

Unlike PRA rcd1 and CLAD, which can be seen in very young puppies, PRA rcd4 may not be visible to the owner or even to the vet or ophthalmologist until later in life. The dog is genetically affected from birth and a DNA test for PRA rcd4 will show this; however the clinical signs of deteriorating eyesight will not be present until sometime later in life and, in fact in a few cases, may never occur. The dog has the defective genes from birth although the clinical signs are not present and this must be understood when considering a breeding programme.

- Explain the meaning of “homozygous for PRA rcd4”.

This is frequently referred to as having “two copies of the mutant gene” and thus being genetically affected.

In layman’s terms this means that the defective gene is inherited from both parents.

If the defective gene is inherited from only one parent the dog will be a “carrier” of the condition which means the defective gene can be passed to the offspring but this dog will never have this condition. This is typical of a recessive mutant gene and most of us are familiar with it in PRA rcd1 and CLAD.

- Remind me what happens if an affected dog is mated to a clear.

AFFECTED to CLEAR >>>>>>>>>> 100% CARRIERS

AFFECTED to CARRIER >>>>>>>>> 50% AFFECTED; 50% CARRIERS

CARRIER to CLEAR >>>>>>>>>>>> 50% CARRIERS; 50% CLEAR

CARRIER to CARRIER >>>>>>>>>> 25% AFFECTED; 50% CARRIERS; 25% CLEA

How do we know there might be 30-40% of dogs in our breed that are carriers?

A random check was performed on a large number of DNA samples stored at the AHT and this provided the information. The large number of samples used by the AHT means that the proportion of carriers for that sample is likely to reflect the proportion throughout our breed.

No. The AHT have permission to use the samples stored for research purposes i.e. in the development of a new test, and to provide a statistical analysis of the results but not to provide individual dog’s names or results.

The way forward is to test the dogs you own now, particularly your breeding stock, and to move forward from this.

The advice so far is to avoid producing genetically affected puppies – if you find you have an affected dog or a carrier with which you wish to breed only breed to a clear dog.

What do we know about another form of LOPRA that exists in the breed?

We know there is a third form of PRA in the breed as 3 dogs have been clinically identified as having PRA but their DNA shows that they do not have PRA rcd1 or PRA rcd4. It probably occurs at a younger age then PRA rcd4. It may be the cause of blindness in the younger dogs that also have the PRA rcd4 mutation. Further research will be needed to find the mutation if more cases are found.

How many dogs so far (July 2011) are homozygous for PRA rcd4

We only know of 7, 6 of which have been named by their owners. I understand that there were very few in the research run but we have not been given further information on this. I do, however, have a personal story to tell as a result of this research run.

My experience has been with my old dog, Willow (Kirkavagh Karamita of Follidown), until now referred to in newsletters but not named because of the uncertainty involved in her condition at the time. During the research she was found to have two copies of (i.e. homozygous for) the PRA rcd-4 mutation and she was blind and she was 13 years old. This seemed to confirm the research programme but on examination by two highly respected ophthalmologists she was found not to have LOPRA. Her blindness was caused by typical problems of old age – some cataract and sclerosis of the lens. If she had lived longer she may have developed LOPRA but, very sadly, she died in April. ( Incidentally, she coped very well in her familiar environment with her blindness but did need extra help and consideration because of her condition.)

Most of you will have read about her already but it provides an important case study and a good reason not to panic if the DNA test shows your dog to be homozygous for PRA rcd-4. Your dog may never go blind despite having the genetic mutation.

If you have any further questions, please email me and I will try to help.

Gillian Townsend

ISAE Health Representative.

Email: townsend@waitrose.com

*********************

A statement from the Irish Setter Breed Clubs Health Coordinators Committee concerning

Late Onset Progressive Retinal Atrophy (LOPRA)

Recently, DNA samples from Irish setters diagnosed with Late Onset Progressive Retinal Atrophy (LOPRA) have been submitted to the Animal Health Trust for genetic analysis. So far several dogs have been diagnosed with two copies of the rcd-4 mutation (i.e. homozygous). This means these dogs are clinically affected with a condition that has previously been described in Gordon setters.

The Animal Health Trust is hoping to release a DNA test for rcd-4 in Irish setters in the near future and when it is available the scale of the problem in the breed can be assessed and an appropriate strategy to eradicate the condition can begin. Until that time the Committee advises against panic and ill‑informed rumour.

Whilst the recognition of LOPRA in the breed is a serious and unwanted development, we should take heart that previous genetic problems (e.g. PRA rcd-1, CLAD) in the breed have been conquered by dedicated breeders implementing controlled breeding schemes, and there is no reason to doubt an eradication programme, when launched, will be successful.

Professor Ed Hall

Chairman, Irish Setter Breed Clubs Health Coordinators Committee

**************

Irish Setter Breed Clubs Health Coordinators Committee

Late Onset Progressive Retinal Atrophy (LOPRA)

Following the discovery of Irish setters clinically affected with LOPRA in association with two copies of the rcd-4 gene (i.e. homozygous), so far the following six dogs (in alphabetical order) have been identified as affected.

- Joben Midnight Memories

- Joben Midnight Moments

- Konakakela Red Admiral at Ixia

- Millcroft the Moon’s Shadow

- Starchelle Buddy Holly

- Wickenberry Capsicum

These names are being published with the permission of their owners/breeders in a spirit of openness in order to alert responsible owners and breeders and to prevent the propagation of unfounded rumours.

Professor Ed Hall

Chairman, Irish Setter Breed Clubs Health Coordinators Committee

Late‐onset (rcd‐4) progressive retinal atrophy in Irish Setters: Where are we, and where do we go from here?

Jerold S Bell DVM Clinical Associate Professor of Genetics Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

We now know from Dr. Cathryn Mellersh at the Animal Health Trust in the UK that there are at least three different inherited progressive retinal atrophy disorders in the breed; and early onset rcd‐1, a still undefined middle‐age onset PRA, and late‐onset rcd‐4 PRA.

The AHT reports a 30‐40% carrier rate worldwide for the defective gene in Irish Setters. The rcd‐4 gene that causes Irish Setter PRA is one that similarly causes autosomal recessive late‐onset progressive retinal atrophy in man. It is the same genetic mutation causing late‐onset rcd‐4 PRA in Gordon Setters. Irish Setter owners will receive affected test results for dogs who have no observable vision problems. This is because this is a late‐onset disorder. It was originally reported that the average onset of this form of PRA was around 10 years of age. This is the average age of Irish Setters recognized with visual impairment that test affected with rcd‐4 PRA. The actual age of onset of Irish Setter rcd‐4 PRA is possibly much older; with many affected dogs never reaching the age of onset of visual impairment. In addition, owners of very old Irish Setters with visual impairment may believe that it is “normal” for old dogs to not see well, and do not pursue a diagnosis of PRA. The fact of the matter is that there is a range of age of onset for the clinical signs of Irish Setter rcd‐4 PRA where some may slowly lose their vision at younger than 10 years of age, and some many never show clinical signs of a vision problem.

Dr. Cathryn Mellersh of the former AHT is searching for the defective gene causing the middle‐age onset form of PRA in the breed, and is interested in cheek swab samples from affected dogs and their close relatives.

Because there is more than one form of PRA in the breed, and because Irish Setters can also have other disorders of the eyelids, cornea, lens, and retina, the rcd‐4 genetic test does not replace the need for annual CERF examinations of the eyes.

The most important thing that we need to do about rcd‐4 PRA is to not devastate the Irish Setter gene pool with widespread spaying/neutering, and the removing of quality dogs from breeding. Aside from the loss of quality dogs, the breed cannot withstand the removal of 30% to 40% of breeding dogs from the gene pool and maintain breed genetic diversity. This is not the only direct gene test that is available for the breed. We must all recognize that the proper use of genetic tests for recessive disease is to breed quality carrier dogs to quality clear dogs, and replace the carrier parent with a clear‐testing offspring that is of equal or better quality.

If a quality dog that you determine deserves to be bred tests as a carrier, you certainly can and should breed the dog. You must make a decision counter to the emotional reaction when you received the carrier test result. Making a decision to not breed a quality dog based on a single testable gene is not appropriate. As long as carriers are not bred to carriers, no affected dogs will be produced. This is a testable and controllable gene. By dealing with rcd‐4 PRA in an objective and informed manner, we can continue to produce quality Irish Setters and work away from this single gene hereditary disorder. The goal is to slowly decrease the carrier frequency in the population and slowly replace carrier breeding stock with normal offspring. This will take many generations. A genetic test should not alter WHO gets bred, only WHO the dog gets BRED TO.

Lastly, it is important to remember that this is about the dogs. You belong to a community that loves Irish Setters. No one wants to produce carrier or affected dogs. The stigmatizing of breeders and quality dogs due to carrier status is an old, outdated and an unacceptable practice. We need to be able to raise the level of conversation to constructive communication.

In the U.K. the DNA test results are automatically published quarterly by the Kennel Club in the Breed Record Supplement and also monthly on their website:

http://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/health/health-information-and-resources/…

With several genetic tests available and more on the way, we know that there are no “perfect” dogs. By working together you can improve your breeding attitudes, your breeding programs, and the overall health of the Irish Setter breed.

Dr Bell’s original article has been slightly modified, with his permission, to reflect the fact that the results for all KC registered dogs are automatically published by The Kennel Club. This modification is in italics. The rest of the article is as written by Dr Bell.

Three of the more prevalent health issues associated in the Irish Setter world are focused upon in the BHCP. These are:

BLOAT

Bloat is a very serious health risk for many dogs, but especially for large and giant breeds. Unfortunately, the Irish Setter is one of the breeds that is particularly prone, and it is really important that owners are aware of and can recognise the signs so they can contact their vet immediately, day or night, if they think their Setter is bloating. Getting your Setter to the vet immediately is crucial as time is absolutely vital; don’t wait to “see what happens” and certainly don’t wait to see if your dog is better in the morning. Bloat is an emergency and all vets are aware of the importance of seeing the dog immediately.

This is a complex disease which is likely to be the result of environmental influences including diet and stress as well as familial susceptability. Whilst it is not clear whether it is truly inherited, or whether it is a reflection of inherited conformational characteristics, it does mean that the chances of your puppy getting bloat increase if there have been other cases of bloat in the family.

What names is bloat known by?

- Bloat

- Dilatation-Volvulus

- Distension

- Gastric Dilatation

- Gastric Torsion

- Gastric Volvulus

- GDV

- Torsion

- Tympani

These are all names that may be used to describe bloat and are often used interchangeably by owners as they are all stages of Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus (GDV)

What is Bloat?

- Bloat is an unusual accumulation of gas and fluids in the stomach, which is not passed normally through belching or flatulence and which causes abnormal swelling.

- The gas that accumulates is largely swallowed air, and does not arise by fermentation in the stomach. The stomach becomes like a drum (tympani).

- A dilatation is where the stomach is distended but is not twisted.

- Eventually the stomach will not only just dilate but also rotate fully on its long axis, causing a torsion/volvulus.

A bloated stomach affects several other organs in the abdomen by putting pressure on them and by affecting the veins which means blood cannot return to the heart as it should. The spleen may also become twisted. As the stomach gets bigger it puts pressure on the chest cavity which makes it difficult for the dog to breathe. If the stomach twists it can totally or partially block the exit to and from the stomach trapping gas, food and water in the stomach. The stomach’s own blood supply can be comprised leading to death of its wall, rupture and peritonitis. This combination can quickly lead to death as organ failure, low blood pressure and shock all set in.

Symptoms

Not all dogs get all the symptoms so don’t wait to see them all:

Phase 1:

The stomach is dilating but may not have twisted.

- Not acting as normal

- Restlessness and anxiety

- May ask to go outside in the middle of the night

- Swelling of the stomach- feels like a drum and may resonate when tapped gently

- Excessive salivation

- Pacing

- Stretching

- Looking at abdomen

- Whining

- Unproductive retching: attempts to vomit but not bringing up food; sometimes a white, frothy saliva is brought up

Phase 2:

The stomach has twisted and shock is starting to set in

- Abdominal pain

- Very restless

- Whining and groaning

- Pacing

- Unable to settle

- Stretching

- Looking at the abdomen

- Abdomen is enlarged and tight

- Difficulty in breathing

- Panting

- May stand with front legs apart and head down

- Trying to vomit more often

- Heart rate increased to 80 – 120 beats per minute

- Dark red gums

Phase 3:

Shock has developed and death is imminent

- Shallow breathing

- White or blue gums

- Weak pulse

- Abdomen is very enlarged

- Heart rate over 120 beats per minute

- Collapse

Measures thought to reduce the risk of bloat.

- Feeding two or three smaller meals a day rather than one large one

- Avoiding exercise for a couple of hours before and after feeding

- Limiting the amount of water available immediately before and after eating

- Feeding a good quality diet

- Not feeding a meal that swells in contact with water

- If you are changing diet then doing it gradually over a period of a few days

- Making meal times as stress free as possible

- Making sure your Setter is not underweight

- If you have more than one dog and there is a race to finish eating then it is best to separate them

It used to be thought that feeding your dog from a raised bowl helped to prevent bloat but more recent research shows this is not the case.

Treatment

Urgent veterinary attention should be sought if you think your Setter is bloated.

Emergency treatment will comprise intravenous fluids to compensate for shock and decompression of the stomach by a stomach tube. Surgery to correct any torsion will be performed as soon as the dog is stable.

General Information

- Dogs that bloat are generally over 2 years old and the chance increases by the time they are about 4 but this is not always the case. Puppies have been known to bloat and, occasionally, dogs over 10 will bloat.

- Larger deeper chested dogs seem to be most at risk.

- There may be a history of digestive upsets, but this in not always the case.

- Having a first degree relative (i.e. parent, sibling) with a history of bloat seems to increase the chances of bloat.

- There may be a familial association with other dogs who bloat but this is not always the case.

- Stress is a known factor and “happy dogs” are considered to be less at risk.

Prognosis and prevention of recurrence

Bloat is a serious condition, with a mortality rate of approximately 30% even with prompt veterinary treatment, although the prognosis is worsened if treatment is delayed.

Dogs that survive an episode of bloat are at increased risk of repeat episodes. The risk can be significantly reduced by performance of a surgical procedure, called a gastropexy, that fixes the stomach’s position and prevents it from twisting, although it will not prevent further episodes of dilatation. This procedure is performed either at the time of the first surgery, or at a later date if a patient is treated with fluids and decompression initially. It is important that you request that your vet perform this surgery which may be performed.

You may be given the option of laparoscopic gastropexy. Commonly called keyhole surgery it is minimally invasive, faster and has better healing results.

The x rays below, courtesy of the vet who took them, shows the before and after scenario of an Irish setter which bloated. That on the left clearly shows the distended stomach which is the large black mass to the right on the x ray. That on the right was taken after the stomach was decompressed. In this case the stomach hadn’t twisted and a laparoscopic gastropexy was carried out a few days later.

Bloat surveys and research from Purdue University

Raghavan, M.; Glickman, N.W.; Glickman, L.T. The effect of ingredients in dry dog foods on the risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 42: 28-36, January/February 2006.

Glickman, L., Glickman, N., et al. Non-dietary risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in 11 large and giant breed dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 217(10):1492-1499, 2000.

Glickman, L.T., Glickman, N.W., Schellenberg, D.B., Raghavan, M., Lee, T.L. Incidence of and breed-related risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 216(1):40-45, 2000

Schellenberg, D., Yi, Q., Glickman, N.W., Glickman, L.T. Influence of thoracic conformation and genetics on the risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus in Irish setters. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 34(1):64-73, 1998.

Glickman, L.T.; Lantz, G.C.; Schellenberg, D.B; Glickman, N.W. A prospective study of survival and recurrence following the acute gastric dilatation-volvulus syndrome in 136 dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 34(3):253-9, 1998

Schaible, R.H.; Ziech, J.; Glickman, N.W.; Schellenberg, D.; Yi, Q.; Glickman, L.T. Predisposition to gastric dilatation-volvulus in relation to genetics of thoracic conformation in Irish Setters. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 33(5):379-83, 1997

Glickman, L.T.; Glickman, N.W.; Perez, C.M.; Schellenberg, D.S.; Lantz, G.C. Analysis of risk factors for gastric dilatation and dilatation-volvulus in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Medical Association 204(9):1465-71, 1994

Raghavan, M.; Glickman, N.W.; Glickman, L.T. The effect of ingredients in dry dog foods on the risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 42: 28-36, January/February 2006.Bloat surveys and research from Purdue University

Glickman, L., Glickman, N., et al. Non-dietary risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in 11 large and giant breed dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 217(10):1492-1499, 2000.

Glickman, L.T., Glickman, N.W., Schellenberg, D.B., Raghavan, M., Lee, T.L. Incidence of and breed-related risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 216(1):40-45, 2000

Schellenberg, D., Yi, Q., Glickman, N.W., Glickman, L.T. Influence of thoracic conformation and genetics on the risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus in Irish setters. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 34(1):64-73, 1998.

Glickman, L.T.; Lantz, G.C.; Schellenberg, D.B; Glickman, N.W. A prospective study of survival and recurrence following the acute gastric dilatation-volvulus syndrome in 136 dogs. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 34(3):253-9, 1998

Schaible, R.H.; Ziech, J.; Glickman, N.W.; Schellenberg, D.; Yi, Q.; Glickman, L.T. Predisposition to gastric dilatation-volvulus in relation to genetics of thoracic conformation in Irish Setters. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 33(5):379-83, 1997

Glickman, L.T.; Glickman, N.W.; Perez, C.M.; Schellenberg, D.S.; Lantz, G.C. Analysis of risk factors for gastric dilatation and dilatation-volvulus in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Medical Association 204(9):1465-71, 1994

Epilepsy

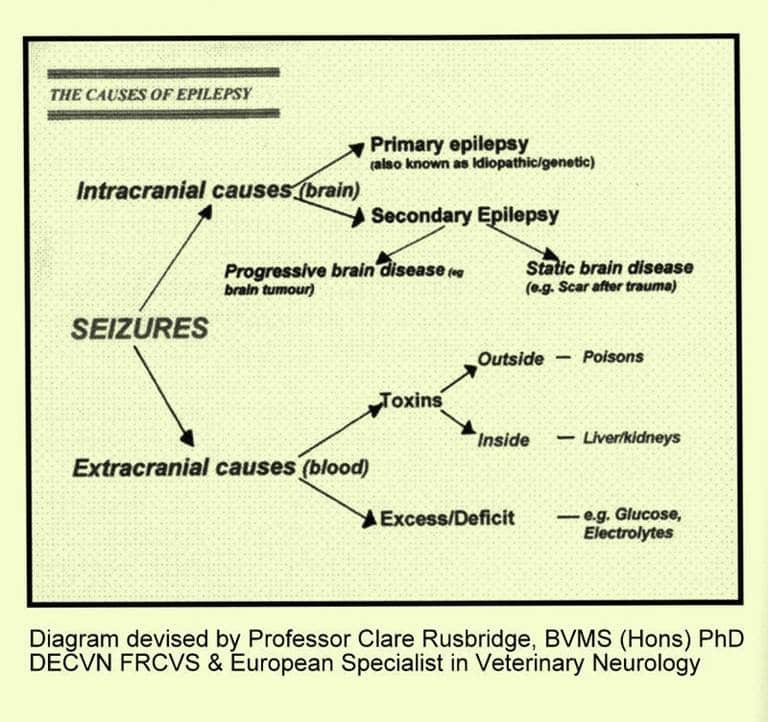

Epilepsy means repeated seizures due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain and is caused by an abnormality in the brain itself. However, a fitting dog is not always an epileptic dog. Fitting or seizures can be caused by a variety of disorders (including poisons, metabolic disorders and brain tumours), with epilepsy being only one of them.

Epilepsy is recognised as an inherited condition (idiopathic epilepsy) in some breeds, and typically signs start between 6 months and 3 years of age.

Signs: Fits occurring during exercise are unlikely to be epilepsy. Epileptic fits usually occur when the dog is quiet and even when rising from sleep: the dog collapses, is unconscious and unresponsive, thrashes it’s legs, often froths at the mouth and can empty its bladder and bowels. It may also scream and moan loudly whilst fitting.

Action: Try to prevent self-injury to your pet, but do NOT attempt to pull its tongue out and never put your face near to a fitting dog; you may be bitten as your dog will not recognise you whilst he is fitting. Some restraint may be necessary, but letting your dog just lie on the floor is probably best, so do not try to move him unless he is in danger. Do not give stimulants. As he recovers he will recognise your voice, so talk to him all the time in a reassuring manner. Time how long the fit lasts and when he has recovered contact your vet; most fits last less than a minute – it just seems much longer. But if a fit does last for more than ten minutes or clusters of fits occur in rapid succession, seek veterinary attention immediately.

On recovery, remove excess saliva and put the dog in a darkened room, keep him/her quiet and warm. Keep a detailed record of your dog’s fits, and let the Breeder know once the diagnosis has been confirmed by your vet.

Further information:

The article on The Kennel Club site was written by Dr Rowena Packer and Professor Holger Volk, both from the Royal Veterinary College.

http://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/health/for-owners/epilepsy/

The Canine Epilepsy Support Group is a small charity set up in 1991 to offer practical and sympathetic support to the owners of epileptic pets, and the opportunity to talk to people who have learnt to live happily with an epileptic pet.

Their Advisory Panel includes Mr Francis Hunter, VetFFHom, MRCVS, Adviser on Homoeopathy, Mrs Sylvia Gulbenkian, BVetMed, MRCVS, Adviser on Acupuncture, and Professor Steve Dean, BVetMed, DVR, MRCVS, Adviser on Veterinary Legislation. The group also works closely with two Herbalists and a Holistic Therapist and they have set out to offer alternative options in addition to prescribed medication and veterinary care. Their aim is to help owners achieve normal, happy lives for their pets and are here to help and support you and your pet.: http://www.canineepilepsysupport.co.uk

The Royal Veterinary College (RVC) runs an epilepsy clinic and if you use the link to the clinic you will find more information: www.rvc.ac.uk/epilepsy

The Canine Epilepsy website is a collaborative project provided by Vetoquinol U.K. and Vetstream. The site contains information on canine epilepsy for both veterinary surgeons and owners of dogs that have been diagnosed with epilepsy: http://www.canineepilepsy.co.uk

The Phyllis Croft Foundation for Canine Epilepsy (PCFCE) was founded to bring comfort, support and information to the owners of epileptic dogs: http://www.pcfce.org.uk/

Megaoesophagus

The oesophagus is the muscular tube that takes food from the mouth to the stomach. This is done by waves of muscular contractions, called peristalsis, which push the food along the tube.

Megaoesophagus (MO) refers to a large, flabby oesophagus which makes it difficult or impossible for food to reach the stomach because the peristaltic action does not happen as it should, probably because the nerves are not functioning properly. Food cannot enter the stomach normally, but instead simply sits in the enlarged oesophagus and is eventually regurgitated.

Some cases of MO in Irish Setters are congenital, i.e. present at birth, but it may not be noticed that the pup has any problem until it is weaned when he will regurgitate food through the mouth and maybe fluids through the nose. It may cough and make gurgling, rattling sounds. An affected pup generally will not thrive and will probably be smaller than his littermates.

MO can also be acquired later in life (about 4 years of age onwards) with similar clinical signs and poor prognosis.

The signs of MO are as follows:

Regurgitation may be considered the most typical sign of MO. Weight loss with possible muscle wasting and a failure to thrive with a general weakness are common. Increased swallowing motions with excessive drooling and dehydration are possible. A ravenous appetite, but with stunted growth or weight loss are usual, as is coughing, difficulty in breathing and pneumonia.

Regurgitation is different from vomiting: Vomiting occurs when the contents of the stomach are expelled by muscular contractions of the abdomen. Regurgitation is purely the return of food that has not reached the stomach and, as such, retching does not happen. As it happens very quickly and with little effort, littermates or mum may clean up the results before the breeder realizes it has happened.

Dogs with MO may not exhibit all of these signs, or even any of them to a significant degree. Sometimes the only signs may be repeated bouts of aspiration pneumonia, or a wet cough that fails to clear up. Some pups with congenital MO can grow out of the disorder and go on to enjoy a normal quality of life, but others will be significantly affected and need careful food management for the rest of their lives. If the problem is severe, however, the pup will not be able to get enough food and will have to be euthanased. Acquired disease, in adult dogs, never resolves.

A definitive diagnosis can be obtained by giving a barium meal. In a normal pup, the barium will move into and through the stomach, but in the dog with MO, most of it will be seen collected in the oesophageal pouch in front of the stomach.

Another congenital reason for regurgitation is a vascular ring anomaly such as persistent right aortic arch. Foetal blood vessels that should have disappeared at birth create a fibrous band that constricts the oesophagus. This causes the oesophagus above the constriction to expand as the food cannot pass through the constricted area. If caught in time, the vascular ring can be cut and the oesophagus often returns to normal. Delaying surgery may cause irreparable oesophageal damage.

Oesophageal dilation and vascular ring anomalies are both believed to have a hereditary component because there is a breed disposition and a probable family predisposition.

If you believe your pet has MO then you will need veterinary advice. If confirmed, it is important to let your breeder know as well as the secretary of one of the breed clubs as information is being collected on the problem.

Megaoesophagus is one of the twenty inheritable gastro-intestinal diseases listed in the Merck Veterinary Manual and is listed as a severe trait in the “Hierarchy of Disagreeableness of a Genetic Trait”.

www.merckvetmanual.org/mvm/htm/bc/100419.htm

Follow the next link to an excellent article on MO with clear X rays of a dog without MO and one with MO. There is also a very clear visual of a dog with MO trying to eat

http://www.marvistavet.com/html/body megaesphagus.html/

Sometimes MO doesn’t happen until later in life, maybe through trauma or being associated with other health problems, but this form is not generally a problem with Irish Setters.

Can you help?

If you breed a litter with MO or your puppy is diagnosed with MO please let the Breed Health Committee know, so we can monitor the prevalence in the breed.

Health issues that seem to be on the rise:

Hip dysplasia

Hip dysplasia (HD) is a problem that is seen across many breeds of dogs, but it is more common in the giant and large breeds. It is an abnormality of the ball and socket joint of the hip. The hip is designed so that the ball should fit snugly into the socket allowing it to move freely but securely without causing any damage to the bones. However, damage may occur if there is looseness in the joint because the bones are not properly formed (e.g. socket is too shallow) and the ligaments do not hold the ball in place. The bone will become damaged and eroded which may lead to new bone formation as part of the body’s attempt to stabilise the joint.

Signs – If it is not severe, HD may not cause any obvious signs. If there are signs it may be lameness in one, or both, back legs, or the dog may “bunny hop”, that is move both back legs together, particularly when going up stairs or steps. There may also be stiffness or pain after resting and eventually the dog may be reluctant to move and will certainly not be able to run and play freely. In severe cases the dog will often sit down when not moving around rather than stand. HD usually causes signs first while a dog is still growing and may affect one or both hips. The dog may appear to grow out of the problem as it becomes skeletally mature at 1-2 years of age, only for arthritis to develop and cause pain later in life.

Diagnosis – If you believe your dog has HD the only way to confirm this is by consulting your vet who will recommend an X-ray. The X-ray should be submitted by your vet to a KC/BVA panel which reads the X-ray and gives individual scores for each hip. The maximum score for each hip is 53 giving a maximum total of 106 and the lower the score the better the hips. Each breed has a Breed Mean Score (BMS), this being the average of the total hip scores. The KC encourages breeders to only breed from dogs which have a score lower than the BMS; the BMS for Irish Setters is currently 10. If HD is confirmed then it is important that you let your breeder know.

Veterinary treatment – The treatment for a dog with HD will depend on the severity of the problem and its age. In many cases drugs can relieve pain and increase mobility, but sometimes surgery is required. It is essential to follow veterinary advice, which will include monitoring your pet carefully. Regular exercise is important and swimming is excellent as it allows the dog to exercise without putting weight on its joints and comfortable, warm, dry bedding is also essential.

Management – It is generally accepted that HD is a complex issue because environmental factors as well as several genetic factors are involved. If the parents have poor hips then there is a higher chance of their offspring having poor hips and it is not advisable to breed from a dog with a high hip score. However, the way your puppy is reared is vital and should your puppy have the genetic predisposition then the environmental factors may well influence the degree of severity of the problem. One significant factor is rapid growth and rapid weight gain so it is important that your puppy has the correct food for his age; don’t be tempted to let him become fat as obesity can cause problems with the newly formed bones. There are many puppy foods available which are designed to give your puppy the right amount of nutrition needed and your breeder should have given you a diet sheet. Don’t be tempted to over-exercise your puppy as this increases the chances of developing hip problems. It may be fun to watch your puppy try and get up and down the stairs or steps but again, please don’t allow him to do this too often as it can also make matters worse. Don’t allow him to stand or walk on his back legs until he is mature and don’t encourage him to jump over obstacles. It is also important not to let your dog jump into or out of a car with a high sill such as in some 4x4s. This sounds as though there are a lot of “don’t’s”, but it will be worth taking the trouble not to let him do these things, or at least not in excess.

A hip replacement operation should only be carried out when there is no alternative treatment and then only after discussion with a specialist referral vet.

Below is a link to a short video which includes xrays of normal hips and those from a dog with HD:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HTwi8TRs6z8

Immune Disorders

To understand auto immune diseases it helps to have a basic understanding of the immune system itself.

The immune system is the protective mechanism for the body and is highly complicated. There are basically two parts to it. The first is the purely physical, being the barriers such as the skin or mucous membranes or the chemical, such as the acids in the stomach, which destroy bacteria.

Should this level of defence fail, which it does for any number of reasons, then the body’s next level of defence will kick in.

When a body is invaded, for the first time, let’s say by kennel cough, once the body has realised there is an invader a series of reactions will take place, which will ultimately kill off the virus. However, this does not happen immediately as it takes time for the body to recognise the invader and symptoms for the illness will occur. Once the invader is destroyed, the body switches off the immune reaction. Should the kennel cough return later, the immune response will be much quicker as the cells responsible will recognise the invader and react more quickly.

However, it is important that the body recognises the difference between itself and the invader, so it only attacks the invader. To allow this to happen, the dog’s cells have their own set of molecules on their surface, which the immune system recognises. The invader, on the other hand, has a different set, called antigens, which the immune system recognises as different, and which, when recognised, will cause the immune system to launch an attack on the invader, whilst not attacking its own cells.

It is essential that both the recognition and discrimination parts are working properly for the immune system to function as it should. Usually it works well, but sometimes it goes wrong, either by overreacting or not reacting at all and sometimes it reacts to its own body cells and this is called autoimmunity.

Click on the following link for a more detailed description of the immune system.

http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=2+2101&aid=957

Autoimmune Disorders

There are a number of auto immune diseases, of which some are detailed below. As far as we know, there are no statistics available for auto immune diseases in Irish Setters, but it is believed the incidence is very low. However, it is useful to be aware of them as prompt diagnosis and treatment can make all the difference.

It is generally accepted that auto immune disease is highly complex and there will probably not be one single factor involved. Whilst a litter may have the predisposition to auto immune disease, through its genes, it may never manifest itself, or different littermates may develop different auto immune diseases. There is a highly complex relationship between the genetics, which in itself is not simple as it is believed that several genes are involved, and the environment, possibly including stress, vaccinations and other variables.

It is accepted by many people that there is a genetic factor and therefore it is recommended that should a dog or bitch have an auto immune disease it should not be used for breeding and, ideally, parents of dogs which develop auto immune diseases should not be breed from again. If your Irish Setter is diagnosed with an autoimmune disease then let a breed club know as well as your breeder.

If you are concerned about auto-immune disease or have an Irish Setter that has been diagnosed with an auto-immune disease the following maybe helpful to you.

CIMDA

Jo Tucker had a Bearded Collie who had an auto immune disease and as a result she became very interested in auto immune diseases and wanted to help others who found themselves in the same situation as herself.

She set up CIMDA (Canine Immune Mediated Disease Awareness) for all owners of any dog that has been diagnosed with an Auto-immune condition or for owners who believe their dog might have an autoimmune disease. CIMDA offers help, advice and support to those owners and Jo is very knowledgeable. She is always willing to help and her expertise and guidance has helped to ensure a speedy diagnosis and correct treatment.

Addison’s Disease –hypoadrenocorticism

Addison’s disease is so called because it was Thomas Addison who identified it in the 1800’s. The adrenal glands produce the hormones cortisol and aldosterone which are needed for different functions in the body. One of cortisol’s main functions is to help the body respond to stress while aldosterone helps to maintain the balance of salt and water in the body, which is vital for the functioning of the kidneys. In Addison’s disease, the adrenal glands are damaged and cannot produce enough hormones.

Symptoms:

- fatigue – not wanting to exercise

- muscle weakness

- loss of appetite

- weight loss

- vomiting and /or diarrhea

- increased thirst leading to having to urinate during the night

- bitches might miss seasons

- Because the symptoms are gradual and often vague they can often go unnoticed and make it difficult for a vet to diagnose it easily. If it not diagnosed early then an Addisonian crisis may occur.This could begin with vomiting and diarrhea, followed by collapse and maybe even a coma and the dog needs immediate veterinary treatment.

Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

There are a number of reasons why your dog may be anaemic and AIHA is only one reason, and an unusual one at that. Anaemia occurs when there are low numbers of blood cells, which contain haemoglobin, which carries oxygen around the body. Haemolytic anaemia occurs when there is a destruction of the red blood cells and the body cannot keep up with reproducing new blood cells. This is when symptoms may be seen. Usually the signs are slow and gradual and you may not be aware that your Setter has a problem until it collapses. Signs to look for are:· an increase in heart rate· increased breathing· weakness· lethargy. Not wanting to go out on exercise or to play. Sleeping a lot or lying around a lot when they are normally active.· loss of appetite· pale mucous membranes. It is very easy to see if the gums are pale, they should be a good pink colour and not pale or white.· fever· jaundice, which can be seen by yellow gums or eyes. Immune-mediated thrombocytopeniaThrombocytes are the cells which are responsible for making the blood clot and Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (ITP) is the destruction of these cells. Symptoms:· excessive bleeding after an accident or operation· excessive bleeding when a bitch is in season· bruising· petechiae-very smalls specks of blood on the skin· blood in the urine or stools. Before ITP can be diagnosed other more common diseases must be ruled out. These could include hemophilia or Warfarin poisoning. (Warfarin is used as a bait to control rats). The site linked below lists the different autoimmune disease, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment.

http://www.provet.co.uk/petfacts/healthtips/autoimmunedisease.htm

Pyometra

Pyometra is an infection of the uterus, which needs immediate veterinary attention. If not treated, it will be fatal. Any unspayed bitch can be affected although it is usually found in older bitches and signs are generally noticed 6-8 weeks after her season. If a bitch has had puppies, it will stop her from getting a true pyometra, but she can still suffer a uterine infection.

Causes.

When the bitch is in season, there are hormonal changes to the uterus, which is preparing itself for puppies. She has a bloody discharge, which is normal, and her cervix, which is normally closed, opens slightly to release this discharge before mating takes place. The open cervix can allow bacteria to enter the uterus, which has become an ideal breeding place because repeated hormonal changes during each season have altered its lining.

Open or closed pyometra.

Sometimes the uterine cervix remains slightly open and this is called an open pyometra and is usually easier for the owner to notice as there will be a foul smelling discharge, which is totally unlike her usual discharge. If the uterus closes completely this is a closed pyometra and there is no obvious discharge. This makes it more difficult for an owner to realise there is a problem and by then the infection could be severe. This is why it is really important to watch your bitch closely 6 – 8 weeks after her season to see if there are any symptoms.

Signs.

In both open and closed pyometra some of the following may be noticed, but don’t wait to see them all. Sometimes all you notice is that your girl is “off colour” and you can’t be certain as to what is wrong. That is enough to make an appointment with your vet, especially if it is 6- 8 weeks after her season.

- Listless and depressed

- Drinking a lot of water

- Loss of appetite

- Distension of the stomach: particularly in a closed pyometra

- Vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Fever

- Dehydration

With an open pyometra you may also see:

- Cleaning herself constantly under her tail

- Pus on her bedding and on her tail

- Foul smell from the pus

Treatment.

The usual and most effective way to treat pyometra is surgery to remove the womb and ovaries and this is probably what your vet will recommend. The spread of infection during the operation is a great worry and it is likely that antibiotics will also be given. However, there is a new treatment that is now available, which means an operation may not be necessary.

It is important that you watch your bitch closely 6 – 8 weeks after her season as that is the time when you will see the signs. The earlier she is treated the better the chances of her survival.

This link is to Wikipedia, which has photographs, but it is not for the squeamish:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyometra

The following is a link to a scientific paper Canine Pyometra: Pathogenesis, Therapy and Clinical Cases presented by Prof. Stefano Romagnoli, University of Padua, Italy

http://www.vin.com/proceedings/Proceedings.plx?CID=WSAVA2002&PID=2686

Porto-systemic shunts (Liver shunts)

Professor E J Hall

A porto-systemic shunt (PSS) is an abnormal vessel that bypasses the liver so that blood which would normally drain from the intestines (via the portal vein) to the liver is ‘shunted’ directly into the general circulation. This causes significant ill health because of toxins from the gut reaching the brain. Ideally the shunt is surgically corrected.

Shunts are being recognised with increasing frequency in pedigree dogs (and occasionally in pedigree cats). They are most common in giant and toy breed dogs. Occasional cases have been seen in Irish Setters although fortunately this is not (yet) a well known problem in the setter world.

We know that shunts are an inherited condition in the Irish wolfhound, but because of the prevalence in other specific breeds we suspect it is inherited in most cases. The exact genetic defect is not known yet, but work is underway in the USA. However, the mode of inheritance is not simple and parents and littermates may not be affected. However, breeding from parents that have produced affected offspring, or from affected animals cannot be recommended.

This article was written at the request of the Breed Club Health Coordinators with the aim of both raising awareness of this condition, so that cases are recognised and successfully treated, and ensuring appropriate measures to control breeding are applied.

This article draws on a client FAQ sheet given by the author to owners of affected dogs referred to Bristol Veterinary School.

What causes a shunt ?

This is a congenital problem, but although a patient is born with the PSS, signs usually only begin to develop weeks or even months after weaning, as the protein content of the diet increases. It is likely an inherited condition and breeding from affected animals is not recommended.

What does a PSS do to the animal?

A PSS can have a number of consequences:

1.Toxins [including ammonia (NH3)] produced by bacterial fermentation of protein in the intestines are not filtered by the liver and affect the brain. Variable neurological signs of ‘hepatic encephalopathy’ may occur e.g. restlessness, intermittent blindness, aimless wandering, head pressing, disorientation, increased thirst and even fits (seizures) and coma in severe cases.

2. Nutrients are not metabolised by the liver, which remains small. This can lead to stunting of the animal.

3. If the liver fails to produce adequate blood proteins, fluid may accumulate in the abdomen (‘ascites’) giving a pot-bellied appearance.

4. Sometimes the abnormal liver function leads to formation of stones in the kidneys and/or bladder and signs of blood in the urine or even obstruction.

5. Occasionally bacteria escape from the gut and, having evaded the liver, enter the circulation causing periods of ill health and raised temperature.

Where is the shunt ?

There are many anatomical variations on a theme, but in general there are two main types:

1.Intra-hepatic – the vein draining the intestine passes through the liver without dividing. This arises most frequently from failure of a vessel normally only present in the foetus to close. It is most commonly seen in giant breed dogs, and is a surgical challenge to correct.

2.Extra-hepatic – the shunt completely bypasses the liver and enters the general circulation directly via one of several possible routes; porto-caval is the most common type. Extra-hepatic shunts are more amenable to surgical correction.

What is the ideal treatment ?

In an ideal world the PSS is tied off (ligated) surgically, and this can be curative. The success rate varies between 50 and 85% depending on the type of shunt and surgical expertise. At Bristol Vet School, we can also now attempt to treat intra-hepatic shunts by placing an occluding coil via a venous catheter. There is still a risk with this new procedure but even riskier open surgery is not required

In some cases, ligation is not possible, for either medical or financial reasons. These patients are managed medically to control the signs of hepatic encephalopathy. Medical treatment merely reduces the production of toxins and does not correct the shunt.

What can go wrong ?

The aim of surgery is to completely close the shunt. Regrettably it is not always that straightforward:

- The shunt may be impossible to find

- There may be inadequate veins going to the liver (or even none) so that complete closure of the PSS causes excessive back-pressure on the intestines. In mild cases this may cause temporary accumulation of fluid (ascites). In severe cases it can lead to death of the patient, and so the surgery has to be reversed.

- There is a risk of serious haemorrhage, especially with intra-hepatic shunts, which may have to be dissected free of surrounding liver tissue. Placement of a coil by venous access is less risky but not widely available.

If the shunt is found but complete closure is not possible, a partial ligation may be performed. Alternatively a sterile cellophane band placed around the shunt, in order to cause scarring and gradual closure to allow time for the vessels to the liver to regrow.

What is medical management ?

The aim is to reduce intestinal production and absorption of toxins such as ammonia, and so reduce signs of hepatic encephalopathy. Medical treatment is indicated for:

- For short-term stabilisation of patients before surgery

- Patients where ligation of the shunt fails because of a lack of normal vessels going to the liver to cope with the revised blood flow

- Patients where surgery is declined for whatever reason.

There are three lines of treatment

1.Dietary management

A restricted protein diet with carbohydrates as the main energy source should be fed. Veterinary diets such as RCW Hepatic Support or Hill’s l/d are suitable. Alternatively a home-prepared diet consisting of equal parts of boiled rice, pasta or potatoes with low-fat cottage cheese may be fed. IIf blood proteins are low, protein should not be restricted severely, and other methods must be used.

2. Lactulose

This synthetic sugar is a laxative that helps remove the intestinal contents rapidly before significant fermentation occurs. It also decreases the absorption of ammonia. The effect is quite variable, and the dose has to be tailored until the patient produces 2-3 soft motions per day.

3. Oral antibiotics

These help reduce the number of ammonia producing bacteria in the gut lumen.

Treatment is tailored by trial and error to each individual patient until signs of hepatic encephalopathy are controlled. Mild cases may do well on dietary management alone, whilst severe cases may require all three medications.

NB. Cases of PSS must be referred by their vet to other centres offering surgery (including Bristol Veterinary School); owners cannot make arrangements directly.

If your Irish Setter is diagnosed with a liver shunt, which is very rare in the breed, then please let your breeder know.

Entropion

A condition in which the edge of one or both eyelids turns inwards to the eyeball; usually it is the bottom eyelid that turns inwards. The condition causes the eyelashes and outer lid hair to irritate and inflame the cornea. It is very painful and in severe cases corneal ulcers and rupture of the eyeball can occur. If seen in puppies, it is likely to be inherited, but may have other causes in an older dog. Sometimes only one eye will be affected, but then the other may turn later.

Symptoms: Continual watering of the eyes. Eyes looking red. Affected dog may often rub its eye against furniture or your leg. You may also see for yourself that the lid is turning inwards.

Action: Consult your vet as it may require surgery. Also tell your breeder, as affected dogs should not be used for breeding and, ideally, neither should their parents. Your vet should also notify the Kennel Club that they have performed a cosmetic procedure to correct the defect.

Ectropion is the opposite of Entropion and the eyelid turns out.

Laryngeal Paralysis

The condition consists of a degeneration of the nerves, which stimulate the muscles of the voice box (larynx). Paralysis of the larynx is quite common in elderly dogs, especially males, and although the Labrador, Irish Setter and Afghan Hound seem to be particularly susceptible, practically any breed in the middle weight range could be involved.

Signs may go unnoticed because owners expect elderly dogs to slow up and huff and puff a bit when exercising. One or more of the following are the most frequent signs of laryngeal paralysis:

- Noisy laboured breathing

- A moist retching cough

- Changed bark

- Reduced exercise ability

- Episodes of extreme breathing difficulty, especially when exercising in hot weather.

Collapse and death can occur if the loose vocal folds block the airway completely.

If you believe your pet has this problem, it is necessary to see your vet to get the diagnosis confirmed. Treatment is by operation to fix the voice-box in a safe position. In spite of the age of many dogs subjected to surgery, the results are generally excellent.

Following the operation, the dog may be hospitalised for between two to four days, although dogs that bark excessively may be sent home earlier if there is concern they will tear the stitches.

Diet and exercise should be modified for the first six weeks after surgery as advised by your vet.

Although an immediate improvement of the respiratory distress may be evident, the full benefits of the surgery will not be seen for a couple of weeks, when the internal swelling has gone.

Most dogs cough to clear their throats to begin with, following ‘tie back’ surgery. This may be quite frequent in the first week or so, particularly after eating or drinking. The coughing should get less frequent, although a few dogs can cough once or twice a day indefinitely.

Your Help Is Needed.

Vet practices obviously collect and store data on all their patients and until recently this information has not been accessed for any research purposes.

VetCompass, a project run by The Royal Veterinary College (RVC) is changing that. It collects this data from participating practices and is using it to answer questions that will improve companion animal health. Information from vet practices is collected anonymously and is proving invaluable to veterinary research.

Dan O’Neill, who runs the project for RVC, has indicated his willingness to work with engaged breeds via their Health Co-ordinator to feed back data of specific relevance to them. He quoted the example of Cavaliers, who already have such an arrangement. Our Breed Health Co-ordinator, Ed Hall, has indicated our wish to participate.

At the moment VetCompass collects data from around 500 Vet practices in the U.K. and it could be invaluable to our breed for more practices to join the scheme. Dan needs data from at least 1000 Irish Setters before the statistics become meaningful.

Please ask your vet whether the practice has joined the scheme.

The sooner we get the data from 1000 setters, the sooner we will get information. Remember the information forwarded to VetCompass is anonymous.

For full information about the scheme go to: